By Art Haddaway, WaterWorld Editor

Over the last century, steam electric power has become a predominant source of energy for a number of municipal and industrial applications in the United States and across the globe. It relies heavily on the use of both nuclear matter and fossil fuels to generate electricity and meets around 82 percent of the nation's energy needs, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

However, this conventional form of power often produces wastewater effluent with high levels of contaminants, including metals and nutrients such as mercury, lead, zinc, nitrogen and phosphorus, aluminum, manganese, and 30 other similar pollutants, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Further, EPA reports that "steam electric power plants contribute over half of all toxic pollutants discharged to surface waters by all industrial categories currently regulated in the United States under the Clean Water Act."

These contaminants have significantly contributed to a wide range of damaging effects to both public health and the environment, including a rise in cancer and neurological disorders, as well as harm to wildlife and aquatic life. Likewise, the EPA indicates that more than 160 waterbodies across the country are failing to meet state standards; roughly 185 have also been put under fish consumption advisories, and close to 400 potable water supply sources have been degraded as a result of uncontrolled steam electric power wastewater discharges.

To address these challenges, the EPA has proposed revised technology-based effluent regulations for the Steam Electric Power Generating category (40 CFR Part 423). The new rule aims to better control and strengthen primary waste streams at approximately 1,100 steam power plants across the U.S. to minimize wastewater discharges. The ruling would concentrate on available technologies that can replace or retrofit existing infrastructure.

In a free webinar hosted by the EPA in August to outline the organization's directive, Ron Jordan, project manager for the ruling, explained that "these technology-driven limits are intended to create a uniform set of requirements that are based on demonstrated technologies and processes."

The EPA proposed the ruling in April of this year and published it in June, after being last modified in 1982 since its inception over a decade earlier. The limits set forth in 1982 only focused on controlling suspended solids in settling ponds; however, these waterbodies now lack the effectiveness to reject any discharged contaminants, the Agency revealed. In 2009, the EPA conducted a study of the steam electric power sector and concluded that the regulations needed to be adjusted. "The study showed that the effluent guidelines were outdated and have not kept pace with changes that have happened in the electric power industry over the last several decades," said Jordan.

ZIn the beginning stages of the ruling, the EPA surveyed 700 power plants across the U.S. to collect and evaluate pertinent data about their "feasibility, costs and economic achievability" in order to help determine holistic technological requirements for all utilities --as each differs in every aspect of its operation. As noted by the Agency, four regulatory options out of a total of eight were classified as preferred choices that ultimately fluctuate based on the "number of waste streams covered, size of the units controlled and stringency of controls." This proposal would focus on preventing contaminants carried by these waste streams through proven technologies already available such as "chemical precipitation, biological treatment, dry ash handling, or recycling of transport water" that either reduce the amounts of pollutants or completely eradicate them depending upon the type of waste stream and regulatory option used.

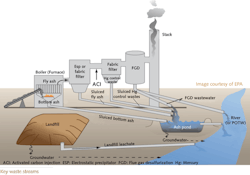

According to EPA, the waste streams contributing the most to discharges are: flue gas desulfurization (FGD) wastewater; sluiced fly and bottom ash; gasification process and sluiced mercury (Hg) control waste; ash leachate; FGD ponds and landfills; and nonchemical metal cleaning excess. Jordan explained that the new guidelines "deal with direct dischargers to the surface waters and their NPDES (National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System) permits as well as the indirect dischargers to the POTWs (publicly-owned treatment works)." In waste streams like FGD wastewater for example, technologies are capable of entirely removing pollutants, and in other torrents such as fly ash transport water, "zero discharge" can be achieved through dry handling methods or recirculation of the water through a closed loop system, according to the Agency.

The EPA predicts that the integration of these regulations would potentially reduce pollutant expulsions by 0.47 to 2.62 billion pounds per year, as well as decrease water withdrawals by 50 to 103 billion gallons, depending upon the type of stream, treatment and regulatory option. Other benefits would include a reduction in nitrogen concentrations, a decline in the production of wet coal ash and an overall improvement of human and aquatic life. The Agency believes the plan is also affordable, would not shut down any utilities and would likely have minimal impacts to future electricity costs.

When it comes to compliance costs, those facilities with coal-fired units (between 66 and 200 of the 1,100) could incur compliance expenditures contingent upon the regulatory option, whereas all 50-megawatt or smaller gas, oil and nuclear utilities would not acquire any costs. Further, the Agency estimated that general annual monetized costs would total between $185 and $954 million with subsequent yearly benefits of between $139 and $483 million.

"The benefits of this rule are quite significant," said Jordan. "EPA has modeled a substantial amount of water quality criteria exceedances in receiving waters... And we anticipate that those would be substantially reduced due to facilities complying with the new effluent limits."

The EPA expects to promulgate a final ruling in May 2014.

About the Author

Art Haddaway

Assistant Editor

Art Haddaway is the Assistant Editor of WaterWorld and Industrial WaterWorld magazines. A writer and editor of over 10 years, he has contributed to a variety of regional publications covering everything from current events to creative features. Art is a graduate of Oral Roberts University in Tulsa, Okla., with a bachelor’s degree in print journalism.